Pew’s methods report and the polling dot-com bubble

We have way more data collection than we did in 2000 but not necessarily more knowledge.

This week, Pew Research Center released an analysis of national pollsters and the methods they have used since 2000. I knew this project was in progress because I had confirmed their information for PRRI in my former role as director of research, and I am very happy to see these results released.

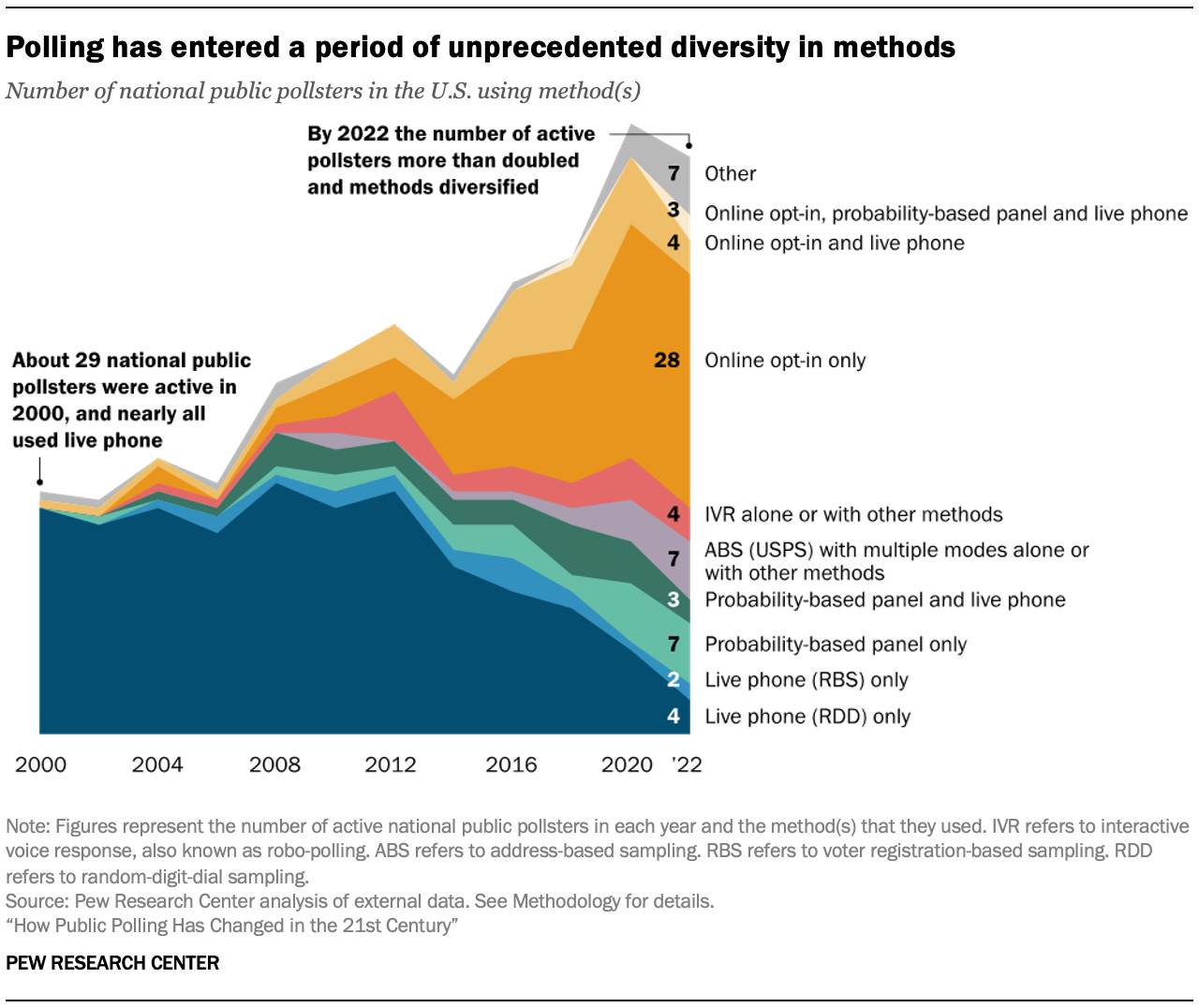

There’s nothing surprising here to those of us in the field; I knew from working on poll aggregation that poll proliferation and the proliferation of dubious methods was a huge problem. The great thing the Pew report does is put it all into stark relief with one key chart.

There are two big things in this chart for which we need to carefully consider the implications:

1. The increase in the number of pollsters

2. The quality of the methods that make up that increase

The increase in pollsters is clear, moving from left to right. The number of public national pollsters active more than doubled from 29 to 69 in 22 years, and the number was clearly over 70 in 2020.1

It’s no accident that as the number of pollsters increased, the methods used diversified, a fact the chart conveys quite well. The internet and less expensive data collection enabled more pollsters to enter the field. In order to explain why that matters, let’s take a step back to what polling looked like in 2000.

Back in my day…2

For a glorious few decades, there was one obvious way to conduct polls: Telephones.3 When most households had a landline telephone, with the number associated with the household determined by its geographical location, pollsters could randomly dial numbers within geographic areas (or the entire country) and get a random sample of people. This is called “random digit dial” (RDD) polling. We knew that the person who always answers the phone might be systematically different from others in the household, so we asked for the adult with the most recent birthday or some other method of in-home randomization. And most people answered their phones, so it worked pretty well.

We were nearing the end of this glorious era in 2000, but it wasn’t over yet. Response rates were declining due to innovations like caller ID that allowed for screening phone calls, and cell phones were beginning to expand into the middle class (unless you lived in the boonies like I did and they were still pointless). The internet was starting to become more a part of life, if not quite daily life yet for most people. Random digit dial phone polling was still the best way to reach people, by far. This is the dark blue area of the chart – few pollsters did anything else in 2000.

As cell phones began taking over more of the market, pollsters were able to adapt by dialing cell phones in addition to landlines for their RDD methods. There was just one huge hiccup: The Federal Communications Commission banned the use of “autodialers” for cell phones. Autodialers are used to dial a lot of phone numbers very quickly and allow pollsters (and others who do lots of phone calls) to only spend time on a call if someone answers the phone, reducing the amount of time and labor needed to dial thousands of numbers looking for people who might be home to answer the phone.

Given that cell phones were pay-per-minute in the early days (and some still are), the FCC restricted unwanted cell phone calls to only those with a human physically dialing the number. The result of that was increased labor costs for interviewers to dial every cell phone number. And as the share of cell phones steadily increased, and many Americans dropped household landlines, pollsters had to dial more and more cell phones. The problem of increased labor costs was compounded by the fact that fewer and fewer people were answering calls from unknown telephone numbers.

The inflection point: 2012

We see in the chart that the balance of cost vs. benefit of RDD telephone polls fell apart rapidly after 2012. The expense of labor and high nonresponse became unsustainable for many pollsters. Live telephone calls using voter registration lists (“registration based sampling” or RBS) were not ever widely used by the pollsters in Pew’s database, but the same principle of phone calls becoming prohibitively expensive due to nonresponse still applies.4

It’s hard to overstate how jarring this disruption has been for the polling industry. For decades, RDD methods worked well for conducting polls, and then within a decade or so it completely fell apart. Polls that use these methods still exist, of course, and still seem to produce good quality data despite the challenges, but only a small handful of pollsters can build their business on it – at least, not solely on RDD.

At the same time, the increasing availability of people on the internet offered alternatives. The problem is that there are few good ways to control who takes surveys online in a way that ensures all populations are adequately represented. The large orange section in the chart represents “opt-in” online samples – meaning, people taking the surveys have specifically volunteered to take surveys. This is a fundamentally different process from telephone polls or other random selection polls, where pollsters have control over respondent selection by choosing the phone numbers. It’s reasonable to assume – and research has borne out – that people who choose to take surveys on the internet are systematically different from those who do not seek out these opportunities.

One way around this is the “probability based panel,” which Pew and others use. In this method, the pollster still chooses the people to recruit to surveys in a two-step process. The first step uses either random selection to contact people by phone or mail and recruit them into taking surveys. Once recruited, those people are in a “panel” that the pollster then samples from for a given survey. By using the random methods for initial recruitment, the panel is “probability based.” This method is represented by the green section in the chart. It is expensive to build these panels, hence the small number of pollsters.

Opt-in internet surveys are by far the most common single method in use in national polls, with nearly half of national pollsters relying on it. There is a lot of variability in opt-in respondent selection. Some opt-in pollsters build their own panels by recruiting online and working to carefully balance their participants in a way that – at least in theory – is close to what the population looks like. These are the better ones. Many of these opt-in polls, however, are using not very well curated sample sources that focus on getting inexpensive data more than high quality data. The argument is that one can set “quotas” (a needed proportion) for demographics like gender, education, race, and so forth, and in that way get a balanced sample.

If that sounds like a questionable way to get data, it is. And there is a lot of data being produced this way – not just in political polling, but in academia and the private sector. Pollsters will claim the data are good quality for the sake of their sales targets and making a profit or generating attention, while knowing that the data are coming from panels full of people that are taking surveys to get the incentives (e.g., gift cards, cash) and not necessarily paying attention to what the survey asks. Bots and fake respondents are also a problem.

The other smaller categories in the chart represent combinations of methods. This may indeed be the future of survey research, as different segments of the population are more easily reached using different methods. A simple example of this is age: Older people will answer their phones, where younger people will not. Younger people might respond to text message polls or internet polls, while older people might not.

All that to say…

I have intentionally avoided using the term “representative” in describing any of this. “Representative” is thrown around so much that it has ceased to have meaning in the field – in fact, if the survey calls itself “representative” I kind of stop paying attention. Pollsters who know explain how it’s representative instead of just throwing the word around.

In the end, what this chart says to me is that we have a lot more data collection happening than we did in 2000 but not necessarily more knowledge about the public being generated.

The junk data problem is massive, and we have a bubble of it.

The good news is that most bubbles are unsustainable over time. I hope that is true of public political polling, but I worry that the trajectory of the media industry means that bad polling will continue to find audiences.

From Pew’s description of the sample: “The organizations analyzed represent or collaborated with nearly all the country’s best-known national pollsters. In this study, “national poll” refers to a survey reporting on the views of U.S. adults, registered voters or likely voters. It is not restricted to election vote choice (or “horserace”) polling.”

I should note that I entered the survey research field in 2006, so I caught the tail end of this, but my career has mostly existed in the upheaval since.

Surveys by mail were and remain a good way to do polls as well, but the weeks-long timeline for mailing out and receiving surveys back has meant that applications in public polling have been limited.

We would likely see more use of RBS in state-level polling since voter registration lists are maintained at the state level. The whole chart would look significantly different at the state level – due to the smaller geographies, it took longer to develop internet panels that were robust enough to use at the state level.